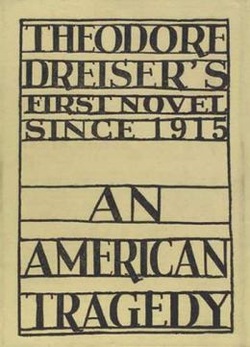

These books were panned primarily because they broke new ground. Innovative writing and unconventional concepts are rarely well received in the short run. (Also honest portrayals of sex, war, racism and other social ills are generally shunned, at least initially.) However, in the long run, these books have stood the test of time, and are now considered classics.

All of these books are on the 100 Best Novels Written in English list.

Although The Great Gatsby earned F. Scott Fitzgerald a mere $13.13 in royalties, The Great Gatsby has been widely hailed as “The Great American Novel.” It was panned by H. L. Mencken in the Chicago Tribune as “no more than a glorified anecdote, and not too probable at that.” Mencken went on to say that the story was “unimportant” and that aside from Gatsby, the characters were “marionettes.”

Aldous Huxley’s biting vision of the future (now officially the present) has become an iconic dystopian novel. Huxley brought us Fordism, The World State, and Soma. When it was published in 1932, the book was not well received. H.G. Wells, regarded as the father of science fiction, wrote that “A writer of the standing of Aldous Huxley has no right to betray the future as he did in that book.” Wyndham Lewis called it “an unforgivable offence to Progress.” Equally disgusted by Huxley’s portrayal of a world controlled by a global capitalist economy, Gerald Bullett concluded that “As prophecy it is merely fantastic.” And not to be bested by other critics,New York Herald Tribune called Brave New World “A lugubrious and heavy-handed piece of propaganda.”

Ralph Ellison’s powerful novel about the experience of black Americans won the National Book Award in 1953, and has since been eulogized as one of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century. Nevertheless,Atlantic Monthly thought it suffered from “occasional overwriting, stretches of fuzzy thinking, and a tendency to waver, confusingly, between realism and surrealism.”

War is pointless, and nobody portrayed that better than Joseph Heller, whose satire, Catch-22,has become so much a part of our national culture that it appears as a lexical item in the Merriam-Webster dictionary. The book was rejected by publishers as “really not funny on any intellectual level.” When it was finally released, The New Yorker had nothing good to say about it. It “doesn’t even seem to be written; instead, it gives the impression of having been shouted onto paper … what remains is a debris of sour jokes”. The New York Times called it “repetitive and monotonous…none of its many interesting characters and actions is given enough play to become a controlling interest.”

No list of chilly receptions would be complete without Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita.

Publishers, who found Lolita“overwhelmingly nauseating,” recommended that it be “buried under a stone for a thousand years.” Its reception upon publication was not much better.

The New York Times pronounced it “not worth any adult reader’s attention … dull, dull, dull … repulsive” and nothing more than “highbrow pornography.”

We’ve all read Lord of the Flies because it has been included in High School English curricula for more than 40 years. (I read it in High School, and I taught it when I became a High School teacher.)

William Golding’s indictment of war (that’s what this book is about) has certainly stood the test of time.

Lord of the Flies, rejected by publishers as “an absurd and uninteresting fantasy which was rubbish and dull,” received a less-than-glowing reception from The New Yorker, which found it “completely unpleasant.”

Arthur Miller’s candid look at sexuality had to be published in France, because it was too risque for the American market. The United States Customs Service even banned the book from being imported into the U.S.

When Grove Press finally published the book nearly 30 years later, over 60 obscenity lawsuits in over 21 states were brought against booksellers that sold it. Pennsylvania Supreme Court Justice Michael Musmanno wrote that it was “not a book. It is a cesspool, an open sewer, a pit of putrefaction, a slimy gathering of all that is rotten in the debris of human depravity.” In kinder and gentler terms, Time magazine described Miller as “a gadfly with delusions of grandeur.”

Ernest Hemingway’s novel about the Lost Generation was initially rejected by publishers as “tedious and offensive.” But the harshest criticism came from his mother, who wrote: “What is the matter? Have you ceased to be interested in loyalty, nobility, honor and fineness in life … surely you have other words in your vocabulary besides ‘damn’ and ‘bitch’ — Every page fills me with a sick loathing — if I should pick up a book by any other writer with such words in it, I should read no more — but pitch it in the fire.”

Richard Wright’s book about a young African-American man living in utter poverty on Chicago’s South Side in the 1930s was an instant bestseller. In keeping with other books that realistically treat uncomfortable social themes, it has been banned numerous times from schools and libraries. Despite its popularity,Native Son was not universally well received. New Statesman found the book to be “unimpressive and silly, not even as much fun as a thriller.”

Theodore Dreiser’s fictionalized account of a notorious 1906 murder has been adapted for theater, screen, radio, opera, and has even been transformed into a musical. When the novel was first published in 1925, it met with the disapproval of the Boston Evening Telegraph, which called its main character, Clyde Griffiths, “one of the most despicable creations of humanity that ever emerged from a novelist’s brain.” Dreiser came under attack as an author whose style was “offensively colloquial, commonplace and vulgar.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed