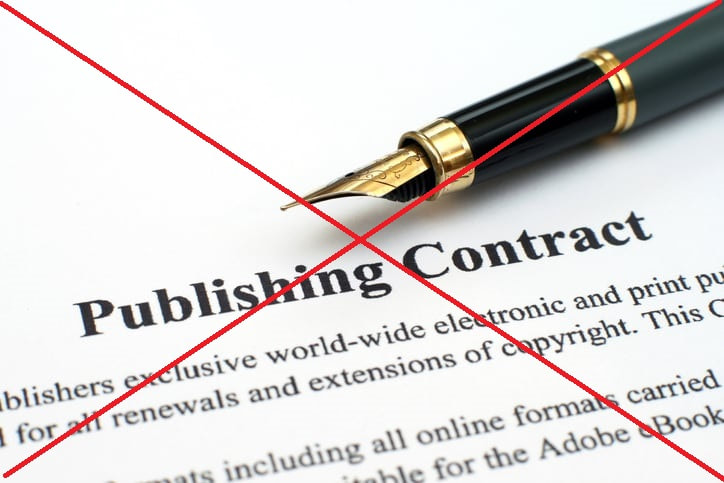

Here are a few of the red flags - taken from real contracts I haven't signed - that should serve as indications that your work deserves to be in better hands.

Rights in Perpetuity

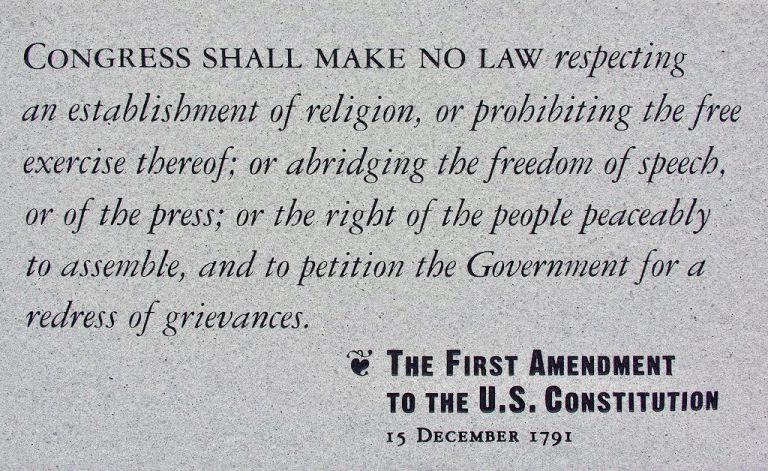

Granting rights "in perpetuity" has become increasingly common in the age of the Internet. The idea is that once your work is published online, it is there "forever." This is patently false. Anything that is published online can be removed. But once you have relinquished all your future rights, you have effectively given away your copyright. Most book contracts now ask for limited rights, either extending until the book goes out of print, or until the author asks to have the rights returned. But some literary journals follow the egregious practice of asking for rights in perpetuity.

Here is an example of a contract clause to avoid:

"The Author grants the Publisher ... perpetual, royalty-free, worldwide rights to copyedit, publish, translate and distribute in all electronic and print formats ... in all languages throughout the world."

(I've left out the long list of every format, but suffice it to say that with this initial clause, the Author has forfeited all rights.)

It gets worse.

On page two of the contract, Article 5 stipulates that "If the Publisher changes its legal form, is acquired by another entity, or otherwise changes ownership, all rights and responsibilities granted in this Agreement will be transferred to the succeeding entity."

Not only does the publisher retain all rights, but any succeeding publisher does as well.

When I received this contract from Six Hens Publishing (a contract that was actually longer than the CNF piece I sent them), I immediately contacted the editors and explained why I could not sign. "But a lawyer drew it up!" they protested. That was precisely the problem. A lawyer's job is to obtain the best possible terms for the client, not to further the lofty aims of literary achievement.

So, how should a contract for short work be worded?

One sentence: "All rights revert to the author upon publication." Sometimes a literary journal will request a short period of exclusivity. That's perfectly reasonable. It is also reasonable, and courteous, to mention the first publisher when you submit your work as a reprint elsewhere. Paying journals should state how much they are paying you, and when. But if the contract is longer than a paragraph, run away.

Requiring authors to do their own marketing

Small book publishers will sometimes require that the author market their own book. While authors are certainly encouraged to promote their work, this should be in addition to everything a publisher does. After all, the reason writers sign with a publisher is precisely because they have marketing and publicity channels unavailable to writers.

You won't normally find marketing specifics in the contract you receive. And chances are you will feel so overwhelmed by the sheer length of your contract, it won't occur to you to ask what they do for marketing.

You need to ask.

The contract that Touchpoint Press sent me for my YA fantasy, ROWENNA, was fairly standard for the industry. It specified advance (none, in this case) royalty rates, right of first refusal, and many of the other clauses included in contracts from larger publishers. (My contract with Random House was 17 pages long.) I didn't sign it immediately, because I had questions. Specifically, I wanted to know what they would do for marketing. This is what I asked:

1) The contract mentions Ingram. What other 3rd party distributors does TouchPoint use?

2) I am pleased to see that there is a clause mentioning libraries. Does Touchpoint distribute titles through Overdrive? Are reviews solicited from the major publications received by librarians (Library Journal, Booklist, etc)?

3) To which trade/industry publications does TouchPoint send requests for reviews?

4) In addition to these, does TouchPoint submit a marketing plan to authors? If so, what does a typical marketing plan include?

5) What is TouchPoint's usual advertising budget for marketing/promotion?

Their reply was cut and pasted into my original email (which I considered unprofessional), and while it contained some details, it was essentially generic. But the real clincher was that the books they had published were only getting two or three ratings on Amazon, and no industry reviews at all. If their marketing department had been up to snuff, there would have been far more ratings on Amazon, and certainly reviews.

Charging writers

Vanity presses are businesses that charge people for printing their books. They are completely upfront about what they charge (which can be a lot), because, typically, their customers only want to give a few books to family members and friends. There is no oversight, so what you submit is what they print.

Hybrid presses, on the other hand, portray themselves as a "partnership" between publisher and author. However, in the end they are actually not much better than vanity presses. They charge exhorbitant fees for each publishing function (cover design, editing, printing, etc.) while offering very little of what an author actually needs from a publisher. Though hybrid publishers like to present themselves as selective, in reality they are a form of self-publishing. But instead of keeping 100% of the royalties, authors only get to keep half.

A contract that charges a writer for anything is not a publishing contract. It is a printing arrangement minus the pedigree conferred by a publishing house.

Recommendations

Always read contracts carefully. Book contracts are almost invariably drawn up by lawyers, which means they are long and complicated. Writers need help to understand them. So, if you haven't joined Authors Guild yet, go ahead and join before you start sending queries to publishers. Authors Guild offers invaluable legal assistance with contracts of all types. (Even if you have an agent, it's worth your while to join Authors Guild. It's always good to get a second opinion,)

Contracts can (and should) be negotiated. In most cases, royalty rates are carved in stone, but if you don't like how a clause is worded, or you would like more author copies, you can make a request for changes. Remember: You are the source of income for publishers. Publishers merely handle what you produce.Do your homework. Look up books the publisher has published. Do they have reviews? Are the covers professional, or do they look cobbled together from open source images? How many books have they published? Are they all written by staff members? Look "inside" a few of them on Amazon. Do you spot any editing errors? A small publisher is not necessarily a bad publisher, but be aware that their resources may be limited.

Last, but not least, Google them. Have other writers posted good or bad experiences with the publisher?

Forewarned is forearmed.

Further reading

Publishing Contracts: What Are Some Red Flags?

When Your Publishing Contract Flies a Red Flag: Clauses to Watch Out For

Red Flags That Authors Should Be Aware of With Contracts

A Publishing Contract Should Not Be Forever

IMHO: A Nuanced Look at Hybrid Publishers

RSS Feed

RSS Feed