But what are resolutions for, if not to be broken almost immediately?

Still, in an effort to be true to my word, I have turned my writerly eye on Susanna Clarke. Clarke gained fame for her masterful Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, a work which took her ten years to write. It was later made into an equally masterful series, which I have watched four times. (Maybe five ... I've lost count.) Rather than tackling Clarke's work with her most famous novel, I began with her second novel, Piranesi, which was published last year, sixteen years after Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell. Clarke takes her time producing a novel, and there is a good reason for that. Her intellect, and the sheer meticulousness with which she constructs a novel, is daunting. I honestly don't know how she holds it all in her head.

Clarke breaks ALL the rules.

By this, I mean the writing rules that I personally adhere to. (I ignore everyone else's rules.) My number one writing rule is: Situate the reader. Right at the beginning, make readers aware of when and where they are, and who the narrator is. Apparently, Clarke has not heard about my rule. Not only does Clarke leave us totally in the dark for a significant portion of the book as to when, and especially where, we are, we actually don't know who (in the conventional sense) is telling the story until it is nearly at its conclusion. I was so disoriented, that I nearly put the book in the beginning. And then it grabbed me by the throat and wouldn't let go. Because not knowing was intoxicating.

Rather than situate the reader, Clarke plops us into the head of the person telling the story. It is told in first person, so that is relatively easy. But what is so unusual about Clarke's approach is that you, the reader, have no idea what is going on, because the narrator has no idea what is going on. The only way Clarke could pull this off successfully is with a brilliant control of a highly unusual voice. Everything that would normally be accomplished with plot, with back story, with exposition, with dialogue, with description (or at least descriptions that we can understand), is conveyed through voice, and with the dizzying, surreal quality than only a distinctive, atypical manner of expression can produce.

Indeed, the voice is so unusual, and yet so familiar, that it was hard to place. It could have been from the 19th century, or the far future, or of a child, or an adult with an innocence verging on brain damage. This confabulation of a confusing, strange, incomprehensible environment with an ingenuous, almost A. A. Milne-like voice created a completely incongruent, yet engrossing atmosphere, as if we had been plunged into the ocean without warning. What increases this sense of being absorbed is that fact that the entire book is written as journal entries, except for a scant ten pages written in straightforward prose that occur three-quarters of the way through the book. (I confess those ten pages were a relief. Situating the reader when the book is well past the halfway mark made that sense of relief palpable.)

In short, Clarke breaks pretty much every literary convention for how to write a novel. And the result is a work that spins a mystery so captivating that it is nearly impossible to break away from once you get caught up in it. Every clue begs you to read on, like bread crumbs leading you through a dense forest. That is something I would like to master, myself. But there is no way I could produce anything as tightly woven as Piranesi. Neverthless, I did learn something valuable as a writer: More than anything else, a skillful use of voice conveys a mood, a context for all the events that happen along the way. Frank Herbert tells us that story is everything. But a story that does not have voice is merely a catalogue of events. In Piranesi, Clarke has demonstrated that simply through a meticulous control of voice a story can be told vividly, and with all the page-turning quality of an action-packed thriller. Can I do what Clarke did? The answer is a decisive no. But I will surely pay more attention to how my characters sound in everything I write from now on.

Not everyone is of like mind on this point. Author Catherine Baab-Muguira completely disagrees with me. In her article, Find Your Topic, Not Your Voice, she argues that topic is more important. She says that her own writing breakthrough, the one that got her a book deal after a dozen years of trying, came from focusing on topic ahead of voice. (I am tempted to make the rather snide observation that publishers always look for a story line first, and that they rarely give a hoot about literary voice.) Writers can argue incessantly about what is most important in a novel: story, voice, metaphor, topic. But the truth is that the only thing that really matters is the skill of the writer. A writer with sufficient skill, combined with that indefinable quality called talent, can pull anything off. And that is the only real rule of writing: You can do anything, provided you can pull it off. Susanna Clarke certainly can.

***

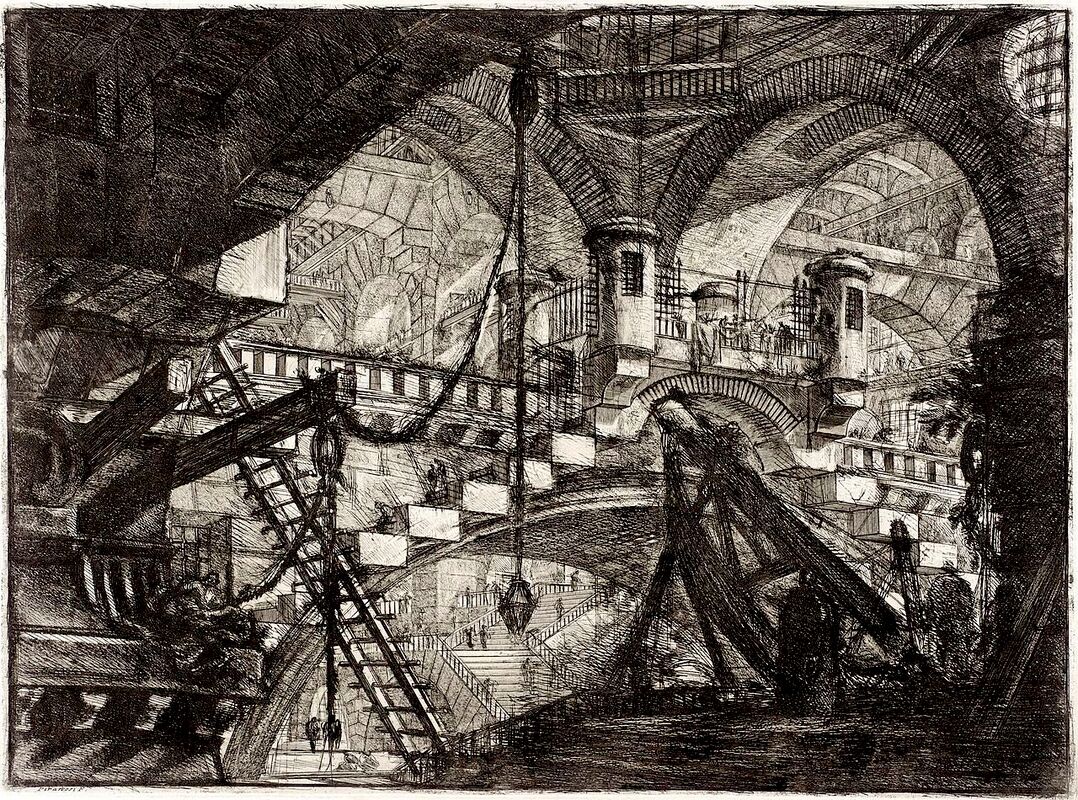

Post script: After I finished reading Piranesi, I decided to look up what that name referred to. The narrator says from the start that he is fairly certain it is not his own name. It has been given to him as a joke by the only other living person in his world. His own name and in fact his entire identity have been forgotten. Clarke does not tell us what that joke is. I only figured out the punchline when I gazed at the fantastical 18th-century etchings of imaginary prisons by Giovanni Battista Piranesi. If you read Clarke's book, you'll get the joke ... and the metaphor.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed