"Let them eat cake"

Squeezing employees - that is, requiring more output while reducing their pay (and benefits) - has been the standard response to economic "corrections" since time immemorial. And, while writers may not feel that they fall in the category of "employee" they are certainly a resource that can be squeezed.

The Authors Guild, in their survey of 1,674 members, reports that since 2009 authors are feeling the crunch; 56% are now making below the poverty line. For a single person, the Federal Poverty Level is $11,770. For a household of two, it is $15,930, and for three it is $20,090. Most of the authors who answered the survey were older professionals (over the age of 50), so we may safely assume that many are married, and/or have children, which means nearly all of the respondents would fall below the poverty line.

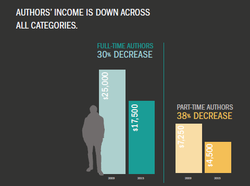

"the median writing-related income among respondents dropped from $10,500 in 2009 to $8,000 2014 in 2014, a decline of 24%. The decline came for both full-time and part-time authors with full-time authors reporting a 30% drop in income to $17,500 and part-time authors seeing a 38% decrease, to $4,500."

Who is hit the hardest?

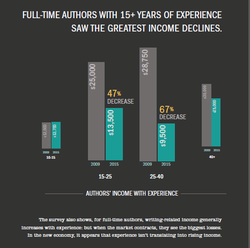

In keeping with the (unwritten) policy of squeezing employees, professional writers, even those with decades of experience, saw a substantial decline in income. While authors with 15 - 25 years of experience lost nearly half their income, those with 25 - 40 years of experience experienced a devastating 67% drop.

This increases the vulnerability of authors with established incomes, as those expenditures can be slashed according to market projections.

For full-time writers the dramatic loss of income may mean having to take on a second job, or even a third, precisely at a time in their lives when they are least likely to be hired.

Retraining for other professions is also difficult for an older population, which means authors may have to take on low-paying menial jobs to make ends meet.

Working as a Walmart greeter is not something a writer expects after 20 years in the industry.

Shifting costs onto the shoulders of writers

Not only are publishers paying their authors less. writers are being asked to foot the bill for their own marketing, which allows publishers to cut publicity costs (and lay off marketing personnel).

In the past, publishers took on the responsibility of marketing and promotion, for which they maintained scores of publicists. The media connections large houses maintained served to offset some of the disadvantages of signing on with a traditional publisher - namely low royalty rates.

Is self-publishing a way out?

The appeal of self-publishing for established authors is obvious. Writers with upwards of 15 years under their belts have experience, not just as writers, but with the industry. They know how the system works. They also have fans. There is no substitute for a loyal following, and any author with a fan base has a distinct advantage over a newcomer - even if both are launching websites, twitter accounts, and social marketing campaigns at the same time.

Fully one-third of the professional writers who took the Guild survey had self-published a book. The attraction of self-publishing has increased exponentially, not only because incomes have dropped, but because alongside the economic contraction, publishers are becoming less supportive of authors. In concrete terms, this means that publishers are imposing restrictions on authors' creativity in order to align their work more closely with what the publisher believes will sell. Publishers base those beliefs not on new, interesting ideas, but on what has sold in the past. No one with an ounce of creativity wishes to be restricted to following the well-worn tracks of previous authors.

What does this mean for new writers?

One of the most attractive things about being a writer is that for the majority of those who take pen in hand (metaphorically, at this point), income is not the motivating factor. People write because: 1) they have a romantic ideal in their head about the thrill of being an author, 2) they really must get a message out to the rest of the world, 3) they like to write. Few anticipate having a meteoric rise to fame and fortune. (Nor should they wish it. Nothing kills a young writer's career faster than early fame.)

Taking into account the dismal findings of the Authors Guild survey, writers must be realistic about their prospects. If publishers continue to cut back on what they offer writers, self-publishing may be the only viable option. Even if new writers don't make a lot of money from their self-published work, at least they don't have a publisher insisting that they cut whole chapters, remove any word longer than two syllables, or rewrite their characters to make them more appealing to 12-year-olds (all of which has happened to me).

There are other options, of course. Forming coops is one of them. Writers who band together have greater chance of success than when each one attempts to make it on his or her own. The cooperative model is one that has existed for decades in other areas of business, why not publishing?

What is abundantly clear from the Authors Guild survey is that something has to be done. Writers are indeed a resource, not just for the industry that profits from them, but for everyone. By reducing authors to penury, we are all the poorer.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed