I listened to the message a second time and recognized the name of my agent – a person with whom I had spoken several years earlier and who had never given me cause for hope. After two years of waiting anxiously by the phone, I had given up on any chance of publishing and reverted to the comforts of vegetal genocide.

I called my daughter and told her about RH.

“Hey,” she said. “I've heard of them.”

“Why are you making that sound?” I replied.

“Well (harharhar), I never thought (harharhar) you'd actually get published (harharharharhar)...”

My daughter is the only person on earth who can produce completely incompatible emotions in me.

And thus begins the first emotional stage of Publication: Ecstasy. The other five stages are: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. I'll get to those later when I talk about contracts.

Before I could say New York Times Bestseller, I found myself scurrying to comply with my agent's agenda. I was instructed to come to The City to lunch with The Editor and to tour RH. I was also instructed to cut my hair and make myself presentable. (This last task proved beyond me.) I got into a car, then on a train, and then not into a taxi (why aren't there ANY available taxis in The City?), and then ran, in the rain, fifteen blocks to RH. By the time I arrived, I was wet, disheveled, and my stockings had fallen down to my ankles.

“You look just like a children's book author should look,” said the agent's assistant. Her lack of irony was unsettling.

There was only one place to sit – a bench made out of something very hard and very unforgiving.

“Just take it in,” said my agent in soft, reverent tones.

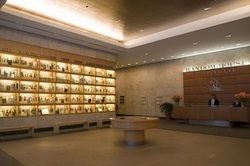

I took it in. We were clearly in the belly of the beast. BERTELSMANN was displayed in large brushed-steel letters on the wall opposite the entrance. There were matching elevators. A bored young person sat behind an enormous bulwark. Behind me was a huge, brutally lit wall encasing the hundreds, nay thousands, of famous books RH had published.

I knew I was in for it.

After receiving permission to ascend, we took the elevator to the 10th floor where I was introduced to my editor, and to 200 other children's book editors. Some of them shook my hand. Others turned their backs (these were the writers of the Golden Books - a disgruntled lot). I met the person who would be in charge of marketing my book. She gave me the look my attire deserved.

Then we went to lunch. My agent had given me instructions to keep my mouth shut. So, I sat there and ate sanitized quasi-Greek food while my editor and agent spoke in hushed voices.

Why hushed?

Because all the other agents and editors in the publishing industry were at adjacent tables trying to eavesdrop on one another's conversations and potentially steal … something. The conversation at my table revolved around “buzz” and other marketing terms. As it turned out, I actually didn't have to say anything, because there was nothing to say. By anyone. RH was a machine, a behemoth, a juggernaut. Nobody could stop it. Nobody could influence it. We were all just tiny teeth in its gargantuan devouring maw.

“The publishing industry isn't just about bestsellers,” I muttered. “Books are ideas. Sometimes you have to take a chance on a new idea.”

My editor leveled her gaze at me and said, without a hint of remorse, that she had turned down J. K. Rowling because her books were “too long, and nobody would read them.”

It was at that point that I began to enter into the next stage of Publication: Denial.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed